ARTICLE Categories

All

|

|

The trees begin to lose their leaves, and you sigh a great sigh of relief thinking that the hay fever and seasonal allergies season is finally over. Then you realise that you are still getting symptoms – itchy eyes, runny nose, a dermatitis flare. It is very possible and even probable that you are suffering from Autumnal allergies.

TV adverts and magazine articles would have you think that hay fever and seasonal allergies only happen in the spring and summer, but that isn’t the case. Autumn brings its own set of allergens ready to trigger a runny nose, atopic dermatitis, and itchy eyes. If it isn’t plant pollen, what are the autumnal triggers that can cause so many issues? Weed pollen, mould spores and house mites are the most common triggers for Autumnal allergies, read on to find out more details and to get my 5 tips to lessen the autumnal allergy symptoms. Weed Pollen Not all pollen producing plants flower in spring. A whole category of weeds flower in the autumn and produce the highly allergenic weed pollen. These plants usually flower from late August until the first frost (usually around the end of November but growing later with climate change). This category of plants includes common weeds found in the UK such as nettles and sorrel but also varieties that are much newer to the UK and Europe such as the American Ragweed. Not only is ragweed a recent invader, but it also produces one of the highest amounts of pollen, causing uncomfortable hay fever and dermatitis symptoms in many sufferers. Mould Spores Mould is around us all the time, but at this time of year levels peak with the falling leaves gently composting on the ground releasing large amounts of allergenic spores. These are the main types of mould which have been highlighted as being triggers for allergy symptoms: Cladosporium Herbarum – this is a black mould that you can sometimes be found on bathroom walls or in a fridge, but it is also found on rotting vegetation. This is the considered the most allergenic of the moulds as it is easily airborne and so can spread quickly. Penicillium Notatum – found in decomposing leaves and soil. This mould is also the type you find on food that is going off eg. bread and fruit. Alternaraia Alternata – mainly found in rotting wood and therefore, forests, but can also be present on food and textiles. Dust Mites Many sufferers of asthma, eczema or hay fever also have a dust mite allergy and whilst dust mites exist all year, reactions tend to peak in autumn as the weather becomes damp but remains relatively warm and we retreat inside and close our doors and windows, but we haven’t yet put our heating on. 5 Tips to Lesson the Autumnal Allergy Symptoms

If you were interested in this article, you may be interested in these other blogs I’ve previously published: Sign up for my news to receive the published articles straight to your inbox. Read more by clicking below to see my previously published articles:

I’m Jessica Fonteneau, the Eczema and Digestive Health Nutrition Expert. I’ve worked with hundreds of clients to help them change their diets, better manage their flares, and find relief. My vocation is to help those with eczema and digestive issues, because I have suffered with these interlinked conditions since I was 6 months old, and I truly know what it is like to experience these debilitating conditions. Every client I have ever worked with has their own triggers and ideal nutrition. There is no such thing as ‘one-size-fits-all’. Whether you work with me one-to-one or use my guided tools, my objective is to help you uncover what works best for you, so that you take back control and experience relief. My guided programmes are only suitable for adults as children have very specific nutrition requirements. I do, however, work with many child clients as part of my clinic. I also offer two free communities for adults caring for children with eczema and digestive symptoms, feel free to come and join us and get some well-deserved support.

To easily keep up with my articles, masterclasses, ebooks and online programmes and receive exclusive access to early bird offers, sign-up to my newsletter. Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com

0 Comments

Blood sugars and continuous blood sugar monitors are all the rage and for good reason. Maintaining a stable blood sugar level isn’t just vital for metabolic health and weight, but also plays a key role in maintaining healthy skin and a normal functioning gut. This article will explore the connections between stable blood sugars and both skin and gut health and will provide practical tips to achieve and maintain this important balance:

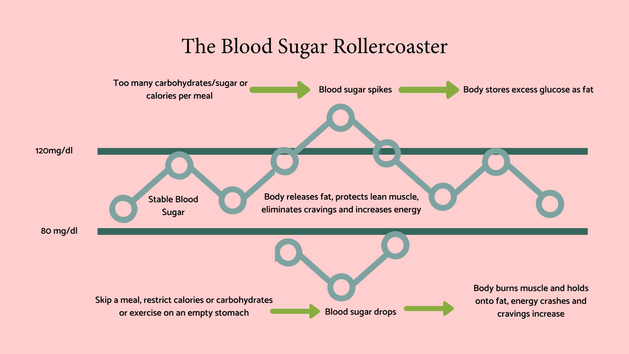

The role of stable blood sugars Before we go into the detail of blood sugar and skin and gut health, here’s a quick overview of how important blood sugars are, so that we put it all in context. Simplistically, blood sugar is our main source of energy, and we get it primarily from eating carbohydrates which our digestive system then breaks down to glucose. This then enters our blood stream and provides energy to cells. Stable blood sugars are vital for lots of reasons, but here are the most cited ones:

Blood sugars and skin health

There are several ways that blood sugars can have an impact on skin health including:

Blood sugars and gut health Blood sugars and gut health aren’t usually associated by most people; however, high blood sugar levels can influence:

My top tips for keeping your blood sugars stable.

I run a 5 day ‘A Week to Reduce Your Sugar Cravings’ Challenge – it’s absolutely free and you can sign up here. Sign up for my news to receive the published articles straight to your inbox. Read more by clicking below to see my previously published articles:

I’m Jessica Fonteneau, the Eczema and Digestive Health Nutrition Expert. I’ve worked with hundreds of clients to help them change their diets, better manage their flares, and find relief. My vocation is to help those with eczema and digestive issues, because I have suffered with these interlinked conditions since I was 6 months old, and I truly know what it is like to experience these debilitating conditions. Every client I have ever worked with has their own triggers and ideal nutrition. There is no such thing as ‘one-size-fits-all’. Whether you work with me one-to-one or use my guided tools, my objective is to help you uncover what works best for you, so that you take back control and experience relief. My guided programmes are only suitable for adults as children have very specific nutrition requirements. I do, however, work with many child clients as part of my clinic. I also offer two free communities for adults caring for children with eczema and digestive symptoms, feel free to come and join us and get some well-deserved support.

To easily keep up with my articles, masterclasses, ebooks and online programmes and receive exclusive access to early bird offers, sign-up to my newsletter. Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com References:

Histamine intolerance is a recently identified but increasingly considered condition that, whilst not life-threatening, can trigger a range of uncomfortable and often debilitating symptoms. The disparity and variety of symptoms that can be attributed to this condition are so widespread that it took time for the scientific community to observe the common denominator, and it is often misdiagnosed in general practice. This, the fifth and last article in my ‘histamine’ series, will delve into this condition that is grabbing the attention of the healthcare community, providing you with information that may help you unravel whether histamine intolerance may be a factor in your health. The article covers:

What is histamine intolerance? Histamine intolerance, also known as histaminosis or histamine sensitivity, is an increasingly recognised condition that affects a significant number of people worldwide. (1,2) is usually defined as the inability to adequately breakdown histamine. Histamine is a neurotransmitter, found throughout the body, but specifically in the skin, respiratory tract, and the digestive system. It is involved in numerous processes including stomach acid production, and vasodilation (the widening of the blood vessels), but is more commonly known for its pivotal involvement in the immune response. It is believed that individuals who suffer from histamine intolerance have a deficiency or dysfunction of the DAO (diamine oxidase) or HNMT (histamine-N-methyltransferase, enzymes, which are responsible for breaking down histamine in the body. This slowing of histamine degradation leads to a possible accumulation of histamine, leading to a variety of symptoms, depending on the individual. It is thought that histamine intolerance prevalence is higher in children than in adults (3), but further studies are needed. My clinical experience, working with many infants and young children with digestive and skin symptoms, is that when true IgE allergies have been ruled out, histamine intolerance is often a route to be explored. Lowering an overall histamine load, rather than assuming that multiple food intolerances are at play, can allow children to retain the all-important macro and micronutrient variety, rather than putting them at risk of strict and restrictive elimination diets which oftentimes worsens the situation and puts their health at risk. Histamine intolerance has, in the past, often been misdiagnosed as whole host of other diseases including food allergy and intolerances, urticaria, eosinophilic gastroenteritis amongst others. When clients come to see me with negative allergy/intolerance testing, but who swear blind that such and such a food triggers a reaction, histamine intolerance is something that immediately springs to mind. Which symptoms hint at a possible histamine intolerance? As I’ve already explored in previous articles (see links at the end of this feature), histamine intolerance can manifest in a variety of different symptoms, hence the diagnosis difficulty. Common symptoms include:

What are the possible contributory causes? There are several possible contributory causes to histamine intolerance, but the main theory involves the concept of an overall histamine ‘load’ or the cumulative effect of several factors, including:

Please note that not every individual will be affected by all the above, and this overview should only support the notion of how your overall histamine load could add up. The genetics of histamine intolerance For some experiencing histamine issues, the question of low or slow DAO or HNMT activity may stem from their genetics. DAO inactivates histamine in the gut and HNMT within the nervous system and lungs. Genetic variants on these enzymes or their pathways can lead to histamine intolerance. Nutrigenomics testing, which I offer through Lifecode Gx, can provide information on our own genes which then informs us on the nutrition and lifestyle changes we can make to align with any variants to optimise health and wellbeing. Lifecode Gx offers a specific Histamine Intolerance test. You can find out more, by clicking the link. Nutrigenomic testing is the only form of testing that is available from the youngest age. Whilst how you eat and live your life will have an effect on whether a gene variation may have an impact, your genes themselves never change. My top tips for lowering your histamine load.

If on medication, please speak to your GP/consultant before making any changes to your diet. If you are interested in histamine and its impact on symptoms, this article is the second in a series I am currently publishing covering. The series in total will include:

Sign up for my news to receive the published articles straight to your inbox. Read more by clicking below to see my previously published articles:

I’m Jessica Fonteneau, the Eczema and Digestive Health Nutrition Expert. I’ve worked with hundreds of clients to help them change their diets, better manage their flares, and find relief. My vocation is to help those with eczema and digestive issues, because I have suffered with these interlinked conditions since I was 6 months old, and I truly know what it is like to experience these debilitating conditions. Every client I have ever worked with has their own triggers and ideal nutrition. There is no such thing as ‘one-size-fits-all’. Whether you work with me one-to-one or use my guided tools, my objective is to help you uncover what works best for you, so that you take back control and experience relief. My guided programmes are only suitable for adults as children have very specific nutrition requirements. I do, however, work with many child clients as part of my clinic. I also offer two free communities for adults caring for children with eczema and digestive symptoms, feel free to come and join us and get some well-deserved support.

To easily keep up with my articles, masterclasses, ebooks and online programmes and receive exclusive access to early bird offers, sign-up to my newsletter. Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com References:

Upcoming programmes and eventsClick on the thumbnails to find out more

It’s a fascinating fact that before puberty, if you are born male, you are more at risk from childhood allergies, but that after puberty those born female are more likely to suffer from conditions relating to immune function including allergies and autoimmune conditions. (1,2)

It’s also reported that many people experience an onset, worsening or sometimes remission from eczema and IBS symptoms at certain times in the menstrual cycle or life stage e.g. pregnancy and menopause. Have you ever considered why? Studies have hinted at the interaction of the neurotransmitter, histamine, and the hormones, oestrogen, and progesterone. Today’s article, the fourth in my ‘histamine’ series, explores this emerging topic and includes:

Histamine, a quick overview Histamine is a compound that acts as both a neurotransmitter and an immune system messenger. It is responsible for a range of roles, including immune response, vasodilation (the widening of the blood vessels), and stomach acid production. Whilst histamine is vital for protecting the bodies against infection and supporting wound healing, too much histamine can lead to various health issues. For more detail on how this might link to digestive health, skin conditions or autoimmunity, please see my previous articles, links below. Oestrogen, progesterone, and the menstrual cycle The menstrual cycle is an intricate ballet of hormonal fluctuations, depending on distinct phases, going from menstruation to the follicular phase, ovulation and finally the luteal phase. During this cycle levels of sex hormones, including oestrogen, progesterone, luteinising hormone, and follicular stimulating hormone, rise and fall with the aim to prepare the body for pregnancy. Oestrogen is a group of sex hormones (estrone, oestradiol and estriol) that plays a key role in the development and functioning of the female reproductive system. Less well considered is the fact that oestrogen also impacts bone health, cardiovascular function, cognitive function, and the modulation of the immune system. Oestrogen levels are at their highest during the follicular phase, between the first day of a period and the next ovulation (days 1-14). Oestrogen is primarily excreted from the body following detoxification via the liver. Some oestrogen is, however, recycled and remains in circulation which may lead to oestrogen levels being proportionately higher at some times. Progesterone, another vital hormone, works in step with oestrogen to regulate the menstrual cycle and prepare the body for a potential pregnancy. It also plays a role in thermoregulation (cooling you down or keeping your warm), skin health, brain function, and vitally has anti-inflammatory actions. Progesterone levels are highest during the Luteal phase of your cycle. This is the phase directly after ovulation which lasts until your next cycle begins. Oestrogen, progesterone, and histamine, how might they interact? Research suggests that histamine levels are influenced by the hormonal fluctuations that happen during the menstrual cycle. Oestrogen has been demonstrated to encourage release of histamine from mast cells. This may explain the increase in symptoms such as allergies, migraines and eczema during the follicular phase, reported by many. (1) Some studies, have indicated that oestrogen may not just trigger mast cells to produce histamine but may also downregulate the production of DAO (diamine oxidase), one of the enzymes that breaks down histamine in the gut. (3,4) Some studies suggest that progesterone may slow mast cells from releasing histamine. (5) Histamine levels linked to the menstrual cycle. A useful, but basic summary, particularly in relation to the topic we are discussing today is the fact that oestrogen can stimulate histamine production and progesterone is anti-inflammatory. If we know that oestrogen levels are highest during the follicular phase and progesterone’s are highest in the luteal phase, then we can start to consider whether a person’s own symptoms can be mapped to their cycle. It is important to note that whilst some do report an increased sensitivity to histamine during certain phases of their cycle, many do not. Histamine and pregnancy Hormone levels are increased during pregnancy and for those sensitive to histamine, an increase in skin or digestive issues may be experienced at that time. Morning sickness can also be related to histamine’s role in stomach acid production. On the other hand, during pregnancy the immune system is naturally heightened, which for some results in remission from eczema or other symptoms for the duration of the pregnancy. Menopause and histamine imbalance The menopause marks the end of the reproductive years and is characterised by a host of hormonal changes including the reduction of oestrogen and the almost total cessation of progesterone production. Remember, oestrogen can induce histamine production whereas progesterone counter acts the effect with its anti-inflammatory role. So, during the menopause when progesterone levels are almost nil, but oestrogen continues to be produced, the scene is set for histamine load to be higher, and many menopause symptoms are directly related to this, including:

My recommendations for keeping histamine in check.

If on medication, please speak to your GP/consultant before making any changes to your diet. If you are interested in histamine and its impact on symptoms, this article is the second in a series I am currently publishing covering. The series in total will include:

Sign up for my news to receive the published articles straight to your inbox. Read more by clicking below to see my previously published articles:

I’m Jessica Fonteneau, the Eczema and Digestive Health Nutrition Expert. I’ve worked with hundreds of clients to help them change their diets, better manage their flares, and find relief. My vocation is to help those with eczema and digestive issues, because I have suffered with these interlinked conditions since I was 6 months old, and I truly know what it is like to experience these debilitating conditions. Every client I have ever worked with has their own triggers and ideal nutrition. There is no such thing as ‘one-size-fits-all’. Whether you work with me one-to-one or use my guided tools, my objective is to help you uncover what works best for you, so that you take back control and experience relief. My guided programmes are only suitable for adults as children have very specific nutrition requirements. I do, however, work with many child clients as part of my clinic. I also offer two free communities for adults caring for children with eczema and digestive symptoms, feel free to come and join us and get some well-deserved support.

To easily keep up with my articles, masterclasses, ebooks and online programmes and receive exclusive access to early bird offers, sign-up to my newsletter. Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com References:

When you think of histamine, you don’t always correlate it with autoimmune conditions, even if you know that those illnesses are all about the immune system and inflammation which is driven by histamine.

Today’s article, the third in my ‘histamine’ series, focuses on autoimmune conditions, and the article includes information on:

Histamine’s involvement in autoimmune conditions Autoimmune conditions are a diverse group of illnesses, which all involve a person’s own immune system mistaking its own tissues as a foreign invader, triggering an immune response, inflammation and ultimately tissue damage. There are a whole host of different autoimmune conditions, affecting diverse parts of the body, including Type 1 Diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Multiple Sclerosis, amongst many others. As an aside, many people mistakenly think that eczema/dermatitis is also an autoimmune condition, but whilst the immune response is involved, it doesn’t actively attack the skin. The precise causes of autoimmune diseases are complex, multifactorial, immunological, and often genetic. Recent research has highlighted histamine’s role in the development and exacerbation of autoimmune conditions (1) and whilst it can’t be blamed solely for triggering autoimmunity, it can act as a catalyst, amplifying immune responses and promoting the inflammation which subsequently leads to tissue damage. For those who are histamine intolerant, have disruptions in the genetic pathways for the breakdown and removal of histamine, or who may be experiencing a temporary high histamine load, the accumulation of histamine in the bloodstream can trigger a range of symptoms such as headaches, hives, digestive issues and may also exacerbate autoimmune condition specific symptoms. Research has even pointed to histamine intolerance as being linked to autoimmune conditions onset due to the constant low-grade inflammation triggered by the molecule’s presence. Long-term exposure to histamine may lead to an over-stimulated immune system, which can lead to dysfunction and reactivity. (1–3) Histamine can stimulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, signalling molecules that promote inflammation. In some cases cytokine production can become excessive, leading to the chronic inflammation so characteristic of autoimmune conditions. (4,5). This can also lead to a condition called Mast Cell Activation Syndrome, that I will address in a future article. Histamine and the gut/immune axis The gut plays an important role in the immune system and recent research has highlighted histamine’s role in influencing this axis along with modulating dysbiosis and the health of the gut wall (leaky gut). (6) See my previous article for further detail. Which are the autoimmune conditions that are most likely to involve a strong histamine response. Whilst histamine is involved in all autoimmune conditions to one extent or another, there are some conditions that are particularly histamine related, these include:

My top tips for managing histamine in relation to autoimmune conditions.

If on medication, please speak to your GP/consultant before making any changes to your diet. If you are interested in histamine and its impact on symptoms, this article is the second in a series I am currently publishing covering. The series in total will include:

Sign up for my news to receive the published articles straight to your inbox. Read more by clicking below to see my previously published articles:

I’m Jessica Fonteneau, the Eczema and Digestive Health Nutrition Expert. I’ve worked with hundreds of clients to help them change their diets, better manage their flares, and find relief. My vocation is to help those with eczema and digestive issues, because I have suffered with these interlinked conditions since I was 6 months old, and I truly know what it is like to experience these debilitating conditions. Every client I have ever worked with has their own triggers and ideal nutrition. There is no such thing as ‘one-size-fits-all’. Whether you work with me one-to-one or use my guided tools, my objective is to help you uncover what works best for you, so that you take back control and experience relief. My guided programmes are only suitable for adults as children have very specific nutrition requirements. I do, however, work with many child clients as part of my clinic. I also offer two free communities for adults caring for children with eczema and digestive symptoms, feel free to come and join us and get some well-deserved support.

To easily keep up with my articles, masterclasses, ebooks and online programmes and receive exclusive access to early bird offers, sign-up to my newsletter. Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com References:

Histamine is often thought of in relation to hay fever and skin reactions, such as atopic eczema, but did you know that histamine is also implicated in digestive health conditions including reflux, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)?

Today’s article, the second in the series, focuses on histamine and its link to gut health and includes:

What role does histamine play in digestion? Histamine, a neurotransmitter, and immune system mediator, plays a crucial role in a whole range of processes and is found throughout the body, including the gastrointestinal tract. Histamine is released by mast cells and basophils in response to allergens, pathogens, tissue damage, amongst other stimuli and plays a dual role in the digestive system, at times being pro-inflammatory and at others anti-inflammatory. It has several roles including (1):

Which digestive disorders are linked to histamine?

What are the possible triggers of a histamine reaction in the gut?

In summary, here are my top tips for managing histamine as a trigger for gut disorders:

If on medication, please speak to your GP/consultant before making any changes to your diet. If you are interested in histamine and its impact on symptoms, this article is the second in a series I am currently publishing. The series will include:

Sign up for my news to receive the published articles straight to your inbox. Read more by clicking below to see my previously published articles:

I’m Jessica Fonteneau, the Eczema and Digestive Health Nutrition Expert. I’ve worked with hundreds of clients to help them change their diets, better manage their flares, and find relief. My vocation is to help those with eczema and digestive issues, because I have suffered with these interlinked conditions since I was 6 months old, and I truly know what it is like to experience these debilitating conditions. Every client I have ever worked with has their own triggers and ideal nutrition. There is no such thing as ‘one-size-fits-all’. Whether you work with me one-to-one or use my guided tools, my objective is to help you uncover what works best for you, so that you take back control and experience relief. My guided programmes are only suitable for adults as children have very specific nutrition requirements. I do, however, work with many child clients as part of my clinic. I also offer two free communities for adults and adults caring for children with eczema and digestive symptoms, feel free to come and join us and get some well-deserved support.

To easily keep up with my articles, masterclasses, ebooks and online programmes and receive exclusive access to early bird offers, sign-up to my newsletter. Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com References: 1. Chen M, Ruan G, Chen L, Ying S, Li G, Xu F, et al. Neurotransmitter and Intestinal Interactions: Focus on the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13(February):1–12. 2. Rettura F, Bronzini F, Campigotto M, Lambiase C, Pancetti A, Berti G, et al. Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Management Update. Front Med. 2021;8(November):1–19. 3. Zaterka S, Marion SB, Roveda F, Perrotti MA, Chinzon D. Historical perspective of gastroesophageal reflux disease clinical treatment. Arq Gastroenterol. 2019;56(2):202–8. 4. Melgarejo E, Medina MÁ, Sánchez-Jiménez F, Urdiales JL. Targeting of histamine producing cells by EGCG: a green dart against inflammation? J Physiol Biochem [Internet]. 2010;66(3):265–70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13105-010-0033-7 5. Kanikowska A, Janisz S, Mańkowska-Wierzbicka D, Gabryel M, Dobrowolska A, Eder P. Management of Adult Patients with Gastrointestinal Symptoms from Food Hypersensitivity—Narrative Review. Vol. 11, Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022. Every so often a new health buzz word emerges. The new “thing” that, once resolved, will, theoretically, solve everything.

From the questions I get within my community forums or from clients, histamine seems to be the current molecule of interest, particularly in relation to skin, gut and autoimmune issues, but does it deserve this notoriety? There is a lot to unpick regarding histamine, so I have divided the topic into 5 separate articles. The first is published below and the next four will follow over the next month, so keep watching this space or sign-up for my emails to receive the articles direct to your inbox:

What is the histamine and eczema/dermatitis link? Today’s article covers:

What is histamine? Histamine is a neurotransmitter, produced by mast cells, found throughout the body, but specifically in the skin, respiratory system, and the gastrointestinal tract, but also by basophils, a type of white blood cell which is involved in an immune reaction. Histamine is mostly known for its involvement in the immune response cascade (one reaction, causing the next and so on). This neurotransmitter is directly responsible for itching, redness and swelling (inflammation) but is also involved in numerous other processes including stomach acid, contraction of smooth muscle (muscles involved with respiration and digestion amongst others), and the dilation of blood vessels. Whilst histamine, the neurotransmitter, is the main driver, there are four different types of histamine receptors (H Receptors) which determine the type or location of a histamine response. (2,3)

Histamine and the immune system, how does it work? When the body encounters an allergen, be it environmental (pollen or dust mites, for example) or food (e.g., gluten, dairy etc.) the immune system responds by producing immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies which bind to mast cells and basophils which then trigger the release of histamine. Histamine release makes blood vessels dilate resulting in blood rushing to the area and leading to the common signs of inflammation: redness, itching and swelling. Histamine is also involved in the inflammatory response when tissue (or skin) is damaged or infected, causing the blood vessels dilate, drawing blood flow and delivering white blood cells to the damaged area which then help to fight off possible infection. Histamine and eczema/dermatitis – what is the link? Atopic Eczema alone affects an estimated 20% of children and 10% of adults in the Western world (1), which is an absolutely massive number of people. If you suffer from any type of eczema/dermatitis you already know that it is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that can be dry, itchy, and inflamed, all symptoms linked to a histamine response. Most researchers agree that there is a link between histamine and eczema/dermatitis. Histamine triggers inflammation, causing itchiness, redness, swelling and testing has identified that individuals suffering from an eczema/dermatitis flare, have high levels of histamine. What is less clear is what the specific connection is. In other words, just as no two eczema/dermatitis sufferers appear to have the same triggers, the histamine connection may be different for everyone. In terms of current and recent research, the following three links have been specifically examined:

Research suggests that histamine’s role in eczema/dermatitis may go beyond its inflammatory role. Evidence has been found that it may contribute to the breakdown of the skin barrier, resulting in ‘Leaky Skin’, making skin less able to retain moisture and act as a protection against irritants. This means that potential allergens and irritants cross into the body more easily, triggering an immune response. Exploring the eczema types most linked to histamine. As we already know, not all eczema/dermatitis is alike, which means that not all types will necessarily have a histamine link, but those that are include:

In summary, here are my 7 top tips for managing histamine as a trigger for eczema/dermatitis:

Speak to your medical practitioner, Registered Nutritional Therapist or pharmacist adviser for further guidance. If on medication, please speak to your GP/consultant before making any changes to your diet. Histamine Masterclass - 1pm, Thursday 14th September. I will be holding an online Masterclass on histamine on Thursday 14th September 2023 at 1pm - claim your early bird ticket at £10. Don't worry if you can't attend live, you can send your questions in advance and the Masterclass will be emailed to all attendees post the event. Read more:

Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com 1. Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: Global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66:8–16. 2. Buddenkotte J, Maurer M, Steinhoff M. Histamine and antihistamines in atopic dermatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;709:73–80. 3. Patel RH; Mohiuddin SS. Biochemistry , Histamine. 2023;32491722. Eczema, or dermatitis, is a non-contagious, inflammatory (meaning that the body’s immune system is activated) skin condition that usually involves a combination of itching, redness, oozing, raised bumps or blisters. Whilst not all types of eczema are the same, or have the same causes, this article covers their differences and some common food triggers.

Eczema flares can be ‘acute’, meaning that there is a sudden appearance of symptoms usually involving blisters and oozing, or chronic when the symptoms remain long-term but are drier in appearance with scaling and cracking. Most clients I work with report a mixture of both, chronic dryness with periodic acute flares. The above is, however, a generalisation, even dermatologists admit that in many cases, the exact eczema type cannot be diagnosed and that no two people will experience the same environmental or food triggers or the same eczema symptoms[1] Hearing that you have eczema is one thing but there are different types of eczema and these can be triggered by different things, so it is worth knowing the difference. Eczema being eczema, of course, many people have a combination of several types versus just one. Here is a brief description of the main different eczema’s: Contact Dermatitis Contact Dermatitis is an eczema that is triggered by direct contact with an allergen/sensitivity eg. nickel or fragrance. The eczema only appears around the site of the contact such as earrings, a watch, belt buckle, perfume or deodorant. Contact dermatitis usually resolves itself, within 5-7 days, once the irritant has been removed. Atopic Eczema Atopic Eczema is an allergic eczema that is often linked to asthma and hay fever and is particularly linked to itchiness. A blood test for raised IgE levels can be used to see whether a true allergy is present. Interestingly, however, not all patients with diagnosed atopic eczema show raised IgE, some may experience a food/environmental sensitivity or intolerance reaction.

About 20-30% of UK infants are affected by atopic eczema. Issues with a a skin barrier protein, filaggrin, was found, in 2006, to be strongly linked to atopic eczema.[2] Pompholyx (Dyshidrotic) Eczema Pompholyx/Dyshidrotic Eczema is linked to atopic eczema and appears as extremely itchy, pin-prick blisters on fingers and/or toes. Over time the blisters turn into scaling and crevasses often form. This form of eczema creates intense itchiness but scratching only worsens the symptoms. This form of eczema often appears in young adults and can be triggered by warmer weather. Seborrheic dermatitis Seborrheic dermatitis generally appears on the scalp and above the eyes. It is usually less itchy than atopic eczema and has been linked to yeast infections. Discoid (Nummular) Eczema Discoid eczema usually occurs in middle-aged/older men. If this form of eczema appears in younger patients then it is actually a form of atopic or contact dermatitis. This eczema forms in round-shaped patches and may leave a long-term, lighter skin tone patch after the eczema has cleared. Stasis (Venous) Eczema Stasis eczema is often found on the lower legs and is linked to problems with circulation and veins. Medical treatment is linked to resolving the vein condition and applying creams to the eczema. Neurodermatitis (Lichen Simplex Chronicus) Neurodermatitis is when skin becomes thick and leathery due to repeated scratching or rubbing, either as a habit or due to stress and it is usually found in a single patch either on the leg or back of the neck. Topical creams are usually the first line of treatment. A focus on Atopic Eczema and Common Food Triggers For those types of eczema that have an inflammatory, immune system response (atopic, pompholyx, discoid and seborrheic) it is useful to find out what your personal triggers are. It is important to note that eczema triggers are individual, during my many years in practice specialising in this area, I have found some common ground and some surprising triggers. My main advice would be to start keeping a food and symptom diary. This means noting what you have eaten during the 3 days preceding a flare. Here is a link to a free 'Food and Symptom Diary' tool I've prepared. The top 6 categories of foods that my clinical experience has identified as the most common are:

Caution, however, about starting to remove whole food groups from your diet, especially if you considering taking anything out of a child’s diet, as doing so can exacerbate the problem rather than alleviate it. My advice would be to work with a nutrition professional. I’ve also found that certain triggers follow what I could only describe as “trends”. For example, in my list above I have gluten, but truth be told, I am finding that it is featuring less and less as a potential trigger. I am, however, finding that triggers to almonds and soy are becoming much more common. Could this be a case of what we eat the most often has the potential to trigger atopic eczema sufferers more? Only time and research will tell. Read more:

My name is Jessica Fonteneau and as a Registered Nutritional Therapist MSc, I have significant clinical experience in supporting clients with digestive, skin and autoimmune disorders. In addition, I have undertaken further study and training in two specific areas:

www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com [1] Lord RS, Bralley JA (2008) Laboratory Evaluations for Integrative and Functional Medicine, 2nd Edition, Canada. Metametrix Institute [2] Irvine AD, McClean WH (2006). Breaking the (un) sound barrier. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1261200-1202 Do you ever start a diet/exercise routine/healthy habit with the best intentions but after a few days or weeks you start to slip back into your old ways. Do you wish that you could just stay on track? Apart from implementing a change, what are you doing to address your mind-set? Have you ever thought that you could be self-sabotaging thanks to unconscious barriers? How do you think you could find out what is holding you back, even if you aren’t aware of it? We all think that we can just willpower our way through it, but if we have subconscious barriers or values that are at odds with our objectives, all the willpower in the world won’t help us succeed. Let’s say you want to lose weight, but you are a sociable person. You can easily see how your objective and your value (sociability) are at odds with each other. I’ve had clients who are willing to suffer a severe eczema flare, rather than tell their friends that they can’t eat a certain food. Exploring our beliefs and barriers via health coaching, opens the doors for change. The concept of thinking about yourself can be very uncomfortable for most people. I mean why, if you could avoid it, would you want to examine your own navel? The thing is, that unless we do go on a voyage of self-discovery, it is impossible to move forward. Whilst we think that our logical mind is doing all the thinking, it is the subconscious mind that has the control. Our subconscious mind makes decisions based on past experiences, good or bad. It takes in cultural and societal norms. Its whole aim is to keep the status quo, to stick with whatever is comfortable and not rock the boat. Even if the change will bring a more positive outcome. Unravelling the decisions your unconscious mind is making without you even realising, is the way to open the door to change. Also, does this sound familiar? You’ve consulted a nutrition/health practitioner and you have all the information you need to reach your health goals. You leave the appointment all fired up, you do a meal plan, buy the ingredients, follow the plan for the first few days and then…. Life happens. You are invited out to a birthday party, or you have leftovers in the fridge that need finishing. You are travelling for work and there is nothing to buy at the train station apart from fast food options and the examples could go on and on and on. When I speak to my clients about previous attempts at changing their nutrition and lifestyle, a common theme is that when they are faced with these kinds of challenges, everything tends to go out of the window, and they give up. They know the what, but they can’t manage the how. When clients come to me and say that they are finding certain situations tricky when following their personalised health and lifestyle plan, my advice to them is to make an intention. Say you are going to a dinner party. If ahead of time you already make the intention of, let’s say having only one glass of wine, but accepting the nibbles or saying no to the bread but having a small portion of pudding, it’s easier to stick with than trying to make all those decisions on the hoof. After having practised as a Registered Nutritional Therapist for a couple of years, I realised that it wasn’t enough to provide the personalised nutrition and lifestyle plan. My clients needed to understand themselves so that they could be open to long-term change. At this point I trained in health coaching and my practice was transformed. I now offer health coaching as standard as part of my packages. The thing about health coaching is that it does require a person to spend time focusing on themselves. Some clients don’t see the utility or think that it is a form of self-indulgence. Do you think that it is an indulgence? In other words, do you think that spending time discovering more about yourself and why you are attached to certain habits is a waste of time? Do you think that if you just dug deeper and mustered a bit more willpower all would be well? The thing about health coaching is that it opens an understanding about yourself that you can apply to anything. You think that a certain tool might help you snack less and then you realise that you can use the same tool to help you procrastinate at work less. The tools and understanding you gain are with you forever and can be applied again and again as you enter different chapters in your life. It’s a life skill. Think of it like a guided prompt, conversations with yourself and tools that allow you to discover some things for yourself, specifically in relation to habits you have. Let me tell you about Sophie (name changed for privacy). She had just had her second child and wanted to lose the baby weight before going back to work. She was exhausted and didn’t have enough minutes in the day but was motivated to achieve her goal. To start off with I empathised with her lack of time and energy. However, when I realised that she was also struggling to follow the programme and was falling behind on her objectives, it was time to highlight how important the coaching side of the programme was. One of my favourite expressions is ‘you can’t pour from an empty cup’. You can’t help others if you aren’t looking after yourself. By her own admission Sophie was giving her all to her family, but was also short-tempered and impatient, because she had nothing left to give. She was also annoyed and felt guilty that she had invested in the programme but wasn’t getting the hoped-for results. We had a long chat about how devoting time to her own health and wellbeing would bring benefits not only to herself but also to all the family. She started to commit to the coaching exercises and was surprised how much easier and less time-consuming it made the whole process. Long story short, whilst she didn’t quite reach her goal by her self-imposed deadline, she was only just off it and had the benefits of more energy, patience, and serenity. She is also grateful for the tools that she now has for life to keep herself on track. Clients tend to think that health coaching is all about weight loss, but my biggest success was with a client who has been battling atopic eczema since she was 6 months old. Julie (name changed for privacy) came to me because she was desperate. Having atopic eczema flares on her hands and face was stopping her from living her life. She was so embarrassed to go out with puffy eyes and bleeding fingers and she was starting to isolate herself and refuse invitations. The thing is Julie knew that she reacted to certain foods. She had done tests with her dermatologist and had the lab results to prove it. Even with these official diagnoses the fact that eating those foods would ‘only’ trigger her eczema rather than an anaphylactic shock, meant that whilst she avoided those foods at home, she didn’t dare refuse foods when she went to others’ houses. So, she kept triggering the flare and it couldn’t never settle properly, causing pain and unhappiness. Working with Julie in a health coaching capacity made her realise that keeping her own inflammation at bay was critical and that with a little preparation and forewarning, her hosts wouldn’t be offended if she said no to something. She found that her friends were only too happy to find alternatives so that she could fully participate. The coaching also helped her make other changes to her diet that supported her skin health and now flares are rare. So don’t think that health coaching is only good for one thing. It is the key to habit change, whatever the reason you need to change your way of eating. Changing the way, we eat takes time. Firstly, because we have to find our own path of what suits us best, without compromising our health. Secondly because changing our habits in a life context that usually stays the same, takes time and guidance. That is why I’ve created a new online, self-guided course, called ‘Unleash the change. Discover the habits and barriers hampering your efforts’ and it’s for people that want change their habits sustainably and for the long term. The course will be available on 23rd February 2023, and I’ll be offering an amazing early bird price for those who get in early. The ability to pre-purchase will be available from 14th February 2023 and I’m so excited for you to see it because it’s going to help you succeed achieve your health and wellbeing objectives. If you aren’t already signed up for my emails which will be featuring an extra discount on top of the early bird offer, click here

Read more:

Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com If you suffer from bloating, painful, hard to pass stools or infrequent stools (e.g., not every day) you or they may be suffering from constipation.

The most important thing you can do if you think you are suffering from constipation is to consult your doctor. Once you’ve been given the all-clear, it’s time to consider some ways to get things moving naturally. This article will cover:

What is a ‘normal’ bowel transit? All foods break down at different rates, moving through the stomach to the small intestine and onto the colon at their own individual speed. Each ingredient from a meal e.g., protein, vegetables and carbohydrates will each arrive in the colon at different times. None of us is average, but research has found that – on average – digestion happens at the following rates:

One to three bowel movements per day is considered normal. If you aren’t passing a stool daily, then it may be time to introduce things that may set that right. The importance of hydration Drink more water - our stools need to be bulked out with water to pass through the gut smoothly. Drink regularly throughout the day rather than a lot in one go so that you are regularly hydrating yourself and your stools. Fibre, the magic ingredient. Whilst many nutrition facts have changed over the years the one thing that hasn't is the importance of fibre. Did you know that you should be aiming for 30g of fibre per day? The average European can barely make 15g. Soluble and insoluble fibre – what’s the difference? Insoluble fibre is considered gut-healthy fibre because it normalises peristalsis (the muscle movement that carries your food through your digestive tract and out) and adds bulk to your stool, helping prevent constipation. Insoluble fibre does not dissolve in water, which means it passes through the gastrointestinal tract relatively intact and speeds up the passage of food and waste through your gut. Insoluble fibres are mainly found in whole grains and vegetables. Soluble fibre binds with water and forms a gel, which slows down digestion and eases the passing of a stool. Soluble fibre delays the emptying of your stomach and makes you feel full, which helps control weight. Slower stomach emptying may also affect blood sugar levels and have a beneficial effect on insulin sensitivity, which may help control diabetes. Soluble fibres can also help lower LDL (“bad”) blood cholesterol by interfering with the absorption of dietary cholesterol. Soluble fibres can be found in food sources such as oats, peas, beans, apples, citrus fruits, carrots, barley, chia seeds and psyllium. How to get enough fibre An average sized orange contains 3.1g of fibre, a 100g portion of cauliflower is between 1.6g, kale has 3.1g per 100g and raspberries knock them all out of range with 6.5g, so it can be difficult to judge your intake. To make it easy you should aim to eat 7 portions of fruit and vegetables per day. I usually recommend 5 portions of vegetables and 2 portions of fruit. You should also include of nuts, seeds, whole grain breads, cereals, beans, and lentils which all contain decent amounts of fibre to boost your intake. It is important to note that fibrous foods are fantastic, but they do need water to help move them along, so go back to my first recommendation. Don’t forget to hydrate! It’s all in the movement Regular exercise and frequent movement are both vitally important to maintain a healthy lifestyle and a state of equilibrium. Without exercise our bodies become sluggish, and this reflects in the state of our gut and the length of our digestion process. Exercise can also help the mechanical part of digestion, peristalsis. The muscle waves that propel the food from your digestive system to the exit. In summary, here are my top tips for relieving symptoms of constipation: Please do not introduce all these options at once, but gradually add one change at a time and note how you feel.

Speak to your medical practitioner/nutritional therapist or pharmacist adviser for further guidance. If on medication, please speak to your GP/consultant before making any changes to your diet. Read more:

My next newsletter will feature an early bird offer for my brand new online, self-guided course ‘Unleash the Change. Discover the habits and barriers hampering your efforts’. Sign-up now to benefit. Interested in what I do and who I am? Go to my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com |

AuthorI’m Jessica Fonteneau, I’m the eczema specialist and I help people Escape from the Eczema trap. Archives

April 2024

Catégories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed