ARTICLE Categories

All

|

|

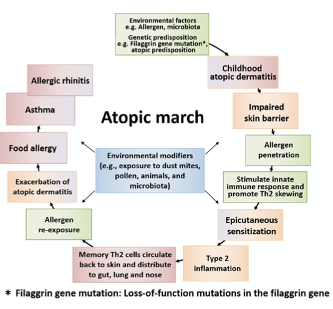

The Atopic March is the term given to the progression of allergic or atopic conditions from infancy into childhood. The ‘march’ usually starts with atopic dermatitis/eczema (AD in babies and sometimes progresses to food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis (hay fever), Don’t panic! Just because there is an atopic march, it doesn’t mean that every infant or child who has AD will go on to develop any of the atopic conditions listed ! Only 60% of children with severe AD go on to experience other conditions within the Atopic March and for those with mild AD, the figure is only 20%. The reasons behind the Atopic March as like those thought to be behind AD generally. A fragile skin barrier that lets possible food or environmental allergens in, triggering the activation of an immune response. Once the initial reaction has been experienced, the body identifies the food or environmental particle as an ‘enemy’ and reactions will manifest either as continuing AD or via other reactions such as hay fever, food allergy or even asthma. (2)

Nutritional strategies for infants and children who may have a familial susceptibility to atopy:

References 1. Tsuge M, Ikeda M, Matsumoto N, Yorifuji T, Tsukahara H. Current insights into atopic march. Children. 2021;8(11):1–17. 2. Yang L, Fu J, Zhou Y. Research Progress in Atopic March. Front Immunol. 2020;11(August):1–11. 3. Davidson WF, Leung DYM, Beck LA, Cecilia M, Boguniewicz M, Busse WW, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;143(3):894–913.

0 Comments

No, it isn’t your imagination that your, or your child’s, eczema is itchier at night. Keep reading to find out more and to get some tips on how to alleviate this occurrence:

Cortisol, the body's natural anti-inflammatory. Levels of our hormones go up and down throughout the day for a variety of reasons, depending on their purpose. One of our main hormones, cortisol is high in the early morning to help wake us up and then lowers as the day progresses until it reaches its lowest level at bedtime, allowing us to become sleepy and have a good night’s rest. Cortisol also has anti-inflammatory effects, which helps naturally dampen eczema’s itchiness and flare. When cortisol levels are naturally low, inflammation will rise, and eczema’s affects will be more readily felt. Hence the night-time itch. The aim for all eczema support is lowering inflammation, often with medication such as hydrocortisone. However, identifying triggers for eczema flares whether environmental, stress or nutrition is ideal for keeping eczema flares and inflammation down. However, they can be tricky to pinpoint, and you should get support from a health or nutrition professional. Some foods are known for their anti-inflammatory properties such as oily fish (sardines, mackerel, salmon), nuts and seeds and green leafy vegetables. Other foods such as ultra-processed foods and drinks can have a more inflammatory effect on the body and so it may be wise to limit those, especially in the evening. Keep cool. For many, temperature differences can be a flare trigger. Too cold and the skin dries and becomes chapped and too hot and the blood vessels nearest the skin barrier, expand, triggering inflammatory cells, raising inflammation, and causing an itch. Consider introducing lighter bed clothes or a weighted blanket with a lower tog if you prefer the feeling of being tucked in. Putting towels in the freezer and then applying them to the itchier parts of the body can be soothing. Natural versus man-made material sheets. Man-made sheets including polyester or nylon are less breathable and can result in more sweating which releases natural body salts which can irritate the skin. Consider investing in cotton or linen sheets which are more soothing to the skin. The only exception to that rule is a wool blanket, the natural lanolin it contains can be extremely triggering for eczema and should, therefore, be replaced with a thin fleece blanket or tucked-in, in a way that so that none of the wool touches the skin. Keep dust at bay. Most eczema sufferers have issues with dust mites and simply dusting the bedroom daily and regularly hoovering under the bed may already lessen a nocturnal flare. Rehydrate. We tend to lose a lot of moisture during the night and so we need to think of hydration both from the inside, by ensuring that we drink plenty of water during the day, but also the outside by moisturising before bedtime to help maintain the skin barrier. If you want to know more about what I do and how I can help, please visit my website: www.jessicafonteneaunutrition.com If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with ‘atopic’ eczema or dermatitis you might be wondering what the ‘atopic’ bit means.

Basically, atopy is the term used to describe those people who develop allergic conditions including allergic rhinitis (including hay fever), asthma and atopic dermatitis/eczema (AD). It usually means that the diagnosed individual has greater immune response, or ‘atopic reaction’ to common allergens including environmental triggers such as pollen and grasses etc.) and food. Atopy versus Allergy Atopy is a Type I hypersensitivity reaction, which means that there is an immediate hypersensitivity to an antigen which results in an over-exaggerated IgE mediated immune response. Allergies are an exaggerated immune response regarding of the mechanism. This means that whilst all atopic reactions are considered allergies, not allergies are considered atopic. Could Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) be atopic? In 2008 scientists published a paper naming a new subtype of IBS, atopic IBS (1). More recent studies appear to confirm the connection between atopy and IBS, with those diagnosed with atopy being at much higher risk for IBS and even Intestinal Bowel Disease. (2,3) Which symptoms are linked to atopy?

Nutrition and atopy Nutrition to support an atopic medical diagnosis will need to be individualised to the food or environmental triggers involved and the specific atopy – skin, gut, lung etc. If you would like to hear more about how nutrition could support your atopy diagnosis, please book in to tell me your story. https://p.bttr.to/2Lh2ifV References 1. Tobin MC, Moparty B, Farhadi A, DeMeo MT, Bansal PJ, Keshavarzian A. Atopic irritable bowel syndrome: a novel subgroup of irritable bowel syndrome with allergic manifestations. Ann allergy, asthma Immunol Off Publ Am Coll Allergy, Asthma, Immunol. 2008 Jan;100(1):49–53. 2. Walker MM, Talley NJ, Keely S. Follow up on atopy and the gastrointestinal tract – a review of a common association 2018. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol [Internet]. 2019 May 4;13(5):437–45. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/17474124.2019.1596025 3. Koloski N, Jones M, Walker MM, Veysey M, Zala A, Keely S, et al. Population based study: atopy and autoimmune diseases are associated with functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome, independent of psychological distress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Mar;49(5):546–55. Atopic eczema or dermatitis (AD) often starts in infancy and the good news is that for most children it spontaneously resolves by the age of seven. However, AD doesn’t like to conform and so for some, AD remains until puberty, may return in later adulthood and for the very unlucky stays with them throughout their lives. Unfortunately for some children, the early onset of AD also signals the start of the ‘atopic march’, with the appearance of hay fever and even asthma, either in tandem with the AD or in some cases instead of (1). In addition, whilst more boys are diagnosed with allergies in childhood, in adulthood women are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with a food allergy and the menopause has been identified as a time when AD flares can either increase or disappear. (17,18). So why do some people get AD? Helping clients with AD is my vocation, as I have suffered from this condition since I was 6 months old. I am so interested in this topic that I have just completed a Master of Science with a dissertation entitled: ‘Examine how nutrition can be used as a complementary tool for the support of eczema/chronic atopic dermatitis (AD)' and I will share some of what I learnt below: Multiple causes have been identified including skin barrier disruption, mutations in the filaggrin gene, gut microbiome (gut bacteria) imbalance, as well as immunological (allergy/intolerances) and environmental triggers, yet there is still no definition of what causes AD. This lack of definitive cause leads to dermatologists and allergy specialists telling their patients that eczema is uncurable and that it can only be modulated by use of corticosteroids and other topical creams and emollients (2,3). There are, however, several areas of research that might shed more light. You may have heard of leaky gut, but it could be that AD sufferers have leaky skin which may be caused by the mutation of a skin protein gene called filaggrin (FLG). Basically, FLG is used to seal the skin barrier and acts to both stop water loss and potential pathogens crossing into the bloodstream. What this means in practice is that whilst the water loss creates the dry, flaky and itchy skin so well-known to eczema sufferers, the ‘leaky skin’ could also be allowing environmental and even food allergens to cross, triggering an immune reaction and inflammation. Up to 48% of AD sufferers have been found to carry this mutated FLG gene (FLG-null-allele) which makes it a very exciting area of research. (4–6). The FLG research has also been linked to another area of AD research, the ‘dual allergen exposure hypotheses’ (12) relating to inappropriate immune response. This area of research suggests that the FLG affected ‘leaky skin’ exposes the AD sufferer to food antigens via touch. The food particle enters the bloodstream via the skin and is quickly identified as a foreigner by the person’s immune system. This causes the body to go into high alert, triggering inflammation and labelling that food antigen as a future threat. A vicious cycle then ensues with the inflammation causing further damage to the skin barrier and leading to even more risk of exposure to food and environmental antigens. Recent studies have found that this type of food antigen exposure can lead to subsequent ingested food sensitivities and intolerances and provides a potential explanation as to why so many AD sufferers know that they react to certain foods, despite negative allergy testing. (13). Studies have shown that child AD sufferers are at higher risk of IgE mediated food allergies but also non-IgE Mediated (delayed) allergies (14). Diagnoses are made via either a blood draw to test for specific IgE antibodies or via Skin Prick Test (15). Other possible tests include the Atopy Patch Test, IgG testing and the Elimination Diet. In children caution must be applied to the Elimination Diet as it is thought that continuous consumption of a trigger food will result in it being better tolerated and that the removal of this food from the diet for a period may result in an increased risk of severe allergy or even anaphylaxis (16). The gut microbiome has become a key research focus within the last decade, both in terms of health generally but also specifically in relation to AD. Intestinal hyperpermeability (leaky gut) and gut microbiome (bacteria) imbalance are linked to worsened immunity, higher rates of inflammation and risk of allergies and intolerances. AD patients have been identified as being at higher risk of both these (10,11). Recently research has started to focus on the skin microbiome (bacterial population). This research has identified that individuals with atopic eczema suffer from skin microbiome dysbiosis (imbalance) with a skew to an overgrown population of staphylococcus epidermidis and staphylococcus aureus (7,8). My clinical experience has often found individual clients who demonstrate a link between both skin and gut dysbiosis (9) and this is an area I am passionate about. Nutritional Strategies As mentioned in the introduction, AD doesn’t like to conform. Whilst there are some common recommendations to all AD sufferers, no two nutrition recommendations are alike, just like no two people’s skin or gut microbiomes are alike. What may work for one, will not work for another. Supporting clients with this condition involves the combining of many pieces of information with practitioner knowledge. Seeking out the individualised manner of eating that allows that person to eat the most varied diet possible, whilst being aware of those foods and environmental triggers that may cause a flare. The main objective is to provide the empowerment that allows for each client to have a sense of control, whilst having the knowledge to face new challenges, in line with AD’s non-conformist tendencies. Below are some of the key nutrients that research has found to be supportive for AD sufferers:

Whilst a deficiency in zinc status has been long thought to be linked to AD, studies using supplementation did not show any benefits (25,26). References:

1. Ring J, Zink A, Arents BWM, Seitz IA, Mensing U, Schielein MC, et al. Atopic eczema: burden of disease and individual suffering – results from a large EU study in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2019;33(7):1331–40. 2. Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: Global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66:8–16. 3. Lopez Carrera YI, Al Hammadi A, Huang YH, Llamado LJ, Mahgoub E, Tallman AM. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis in the Developing Countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East: A Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) [Internet]. 2019;9(4):685–705. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-019-00332-3 4. O’Regan GM, Sandilands A, McLean WHI, Irvine AD. Filaggrin in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(4):689–93. 5. Barbarot S, Aubert H. Physiopathologie de la dermatite atopique. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2017;144:S14–20. 6. Bergqvist C, Ezzedine K. Vitamin D and the skin: what should a dermatologist know? G Ital di dermatologia e Venereol organo Uff Soc Ital di dermatologia e Sifilogr. 2019 Dec;154(6):669–80. 7. Szari S, Quinn JA. Supporting a Healthy Microbiome for the Primary Prevention of Eczema. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;57(2):286–93. 8. Martinez KB, Leone V, Chang EB. Western diets, gut dysbiosis, and metabolic diseases: Are they linked? Gut Microbes [Internet]. 2017;8(2):130–42. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1270811 9. Nakatsuji T, Gallo RL. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy, Asthma Immunol [Internet]. 2019;122(3):263–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2018.12.003 10. Szari S, Quinn JA. Supporting a Healthy Microbiome for the Primary Prevention of Eczema. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019 Oct;57(2):286–93. 11. Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, et al. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms. 2019;7(1). 12. Lack G. Epidemiologic risks for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(6):1331–6. 13. Tricon S, Willers S, Smit HA, Burney PG, Devereux G, Frew AJ, et al. Nutrition and allergic disease. Vol. 6, Clinical and Experimental Allergy Reviews. 2006. p. 117–88. 14. Abuabara K, Margolis DJ. Do children really outgrow their eczema, or is there more than one eczema? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1139–40. 15. Dhar S, Srinivas SM. Food allergy in atopic dermatitis. In: Indian Journal of Dermatology. 2016. 16. Finch J, Munhutu MN, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol [Internet]. 2010;28(6):605–14. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.032 17. Chen W, Mempel M, Schober W, Behrendt H, Ring J. Gender difference, sex hormones, and immediate type hypersensitivity reactions. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;63(11):1418–27. 18. Pali-Schöll I, Jensen-Jarolim E. Gender aspects in food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol [Internet]. 2019;19(3). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/co-allergy/Fulltext/2019/06000/Gender_aspects_in_food_allergy.12.aspx 19. Rusu E, Enache G, Cursaru R, Alexescu A, Radu R, Onila O, et al. Prebiotics and probiotics in atopic dermatitis. Exp Ther Med. 2019 Aug;18(2):926–31. 20. Kim MJ, Kim SN, Lee YW, Choe YB, Ahn KJ. Vitamin D status and efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2016;8(12):8–17. 21. Navarro-Triviño FJ, Arias-Santiago S, Gilaberte-Calzada Y. Vitamin D and the Skin: A Review for Dermatologists. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 May;110(4):262–72. 22. Balić A, Vlašić D, Žužul K, Marinović B, Bukvić Mokos Z. Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan;21(3). 23. Williams HC, Chalmers J. Prevention of Atopic Dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020 Jun;100(12):adv00166. 24. Thomsen BJ, Chow EY, Sapijaszko MJ. The Potential Uses of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Dermatology: A Review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;24(5):481–94. 25. Gray NA, Dhana A, Stein DJ, Khumalo NP. Zinc and atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Jun;33(6):1042–50. 26. Vaughn AR, Foolad N, Maarouf M, Tran KA, Shi VY. Micronutrients in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. J Altern Complement Med. 2019 Jun;25(6):567–77. |

AuthorI’m Jessica Fonteneau, I’m the eczema specialist and I help people Escape from the Eczema trap. Archives

April 2024

Catégories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed